Representing the unrepresented: challenging questions at ICRA's seventh annual conference

The International Catalogue Raisonné Association's seventh annual conference, held at Mishcon de Reya in London on January 8th, 2026, brought together scholars, curators, foundation directors, and legal professionals to examine contemporary challenges in catalogue raisonné scholarship.

Under the theme "The Catalogue Raisonné: Representing the Unrepresented," the conference addressed the systematic exclusion of artists who fall outside the traditional canon of white male European and American figures. In doing so, it asked how catalogue raisonné projects can address the paradox that documenting previously excluded artists risks reconstituting the hierarchical structures that produced their exclusion. And, importantly, if catalogues raisonnés serve scholarship and capitalist market values, can the form be reformed to prioritize the former? The day-long event combined theoretical frameworks with case studies examining institutional practices, alternative funding models, and methodological innovations in documenting previously marginalized artists.

The indispensable and problematic: “Oh, how much I love a catalogue raisonné!”

ICRA Chair Dr. Sharon Hecker opened the conference by addressing fundamental challenges in expanding catalogue raisonné scholarship to include people groups often erased or overlooked in art history. She named the cultural biases and financial constraints that limit the possibility of creating projects that document non-”major” artists, as well as detailing the reasons why such projects are necessary to rewrite the art historical canon.

Image: Rose Palmer of Wild Rose Studios

But there are several key challenges to creating catalogues raisonnés for non-“major” artists. Those major artists—mostly male, white, and financially successful during their lifetimes—had the resources and interest to document their works, process, and career. That documentation forms the heart of a catalogue raisonné. For artists working outside of these systems and without such documentation, creating traditional catalogues raisonnés becomes an incredible challenge. And, as Hecker noted, scholarly works are "only as good as our sources.”

Hecker validated the uncertain nature of research into previously overlooked artists while highlighting challenges posed by privacy legislation and demands for academic transparency. The discussion addressed practical complications rather than idealized research scenarios. In response, she framed catalogues raisonnés not as definitive statements but as provisional beginnings that invite further investigation. This methodological stance informed discussions throughout the conference.

Image: Rose Palmer of Wild Rose Studios

These themes continued through the conference's first keynote presentation, given by Professor Griselda Pollock. Pollock Professor Emerita of Social and Critical Histories of Art at the University of Leeds, applied critical art historical methodology to examining contradictions inherent in the catalogue raisonné form.

She identified catalogues raisonnés as "indispensable but problematic." They bridge the archive and public life, enable critical analysis, yet serve the values of capitalism and function as indices of cultural taste produced through hierarchies of power. She observed that to indicate an artist isn't part of the traditional canon, scholars must add qualifiers, such as “queer,” “female,” “Black,” and “working class.” But this practice paradoxically removes artists from these groups from the category of artist "du Coeur." These qualifiers also quickly increase wordcounts and require expanded documentation.

Her argument centered on opening up the field rather than assimilating marginalized artists into existing white male paradigms. This approach represents what she termed a critical form of inclusive art history. Pollock traced how catalogue raisonné historiography has centered on "the artist as sole originator of art, hence not only the source of meaning but meaning itself." By analyzing this historiography, scholars can examine how exclusion and effacement function within art historical discourse.

The keynote also addressed the role of financial considerations in determining whose art history receives documentation. Pollock cited examples of catalogue raisonné work by Adelyn Dohme Breeskin and other scholars from the 1920s and 1930s, as well as contemporary projects on artists like Lee Krasner and Alma Woodsey Thomas. Her position, which she characterized as "equivocal but definitely critical," examined how creating catalogues raisonnés today can inadvertently reconstitute historical hierarchies even as they attempt to address exclusions.

Situating the catalogue raisonné in its system of forces: “Gender and value bias and the catalogue raisonné”

Image: Rose Palmer of Wild Rose Studios

The conference's first panel examined how institutional forces interact with the catalogue raisonné form and the field, highlighting the multiplicity of value types, value’s relationship with the market, and, importantly, the impact of a catalogue raisonné on wider society. Foundational definitions of value — including market value, social value, aesthetic value, and relational — were provided by an introduction from Linda Selvin, executive director of the Appraisers Association of America.

These types of values don’t always correspond with one another in real life. Professor Renée Adams from Oxford's Saïd Business School presented empirical research demonstrating that gender bias correlates with value bias in the art market. Through a range of research projects, Adams showed evidence that patterns of preferential male treatment exist in measurable terms, that female artists fare better in societies with greater gender equality, and that structural factors rather than individual choices shape the economics and legacies of artistic careers

The legal vulnerabilities created by the absence of catalogues raisonnés for less-famous artists were brought into the conversation by Simon Chadwick, a partner at Mishcon de Reya. Forgery, he noted, disproportionately affects artists without established documentation. This issue called back to Pollock’s address, in which she categorized the erasure of “nonwhitemale” artists as a criminal act. In this specific example, the lack of a catalogue raisonné itself is a form of criminality because it leaves artists and their estates exposed. His work with Indigenous artists and neurodivergent artists highlighted how catalogue raisonné projects must now integrate wider cultural differences and perspectives into their publications to protect these artists and ensure their economic justice.

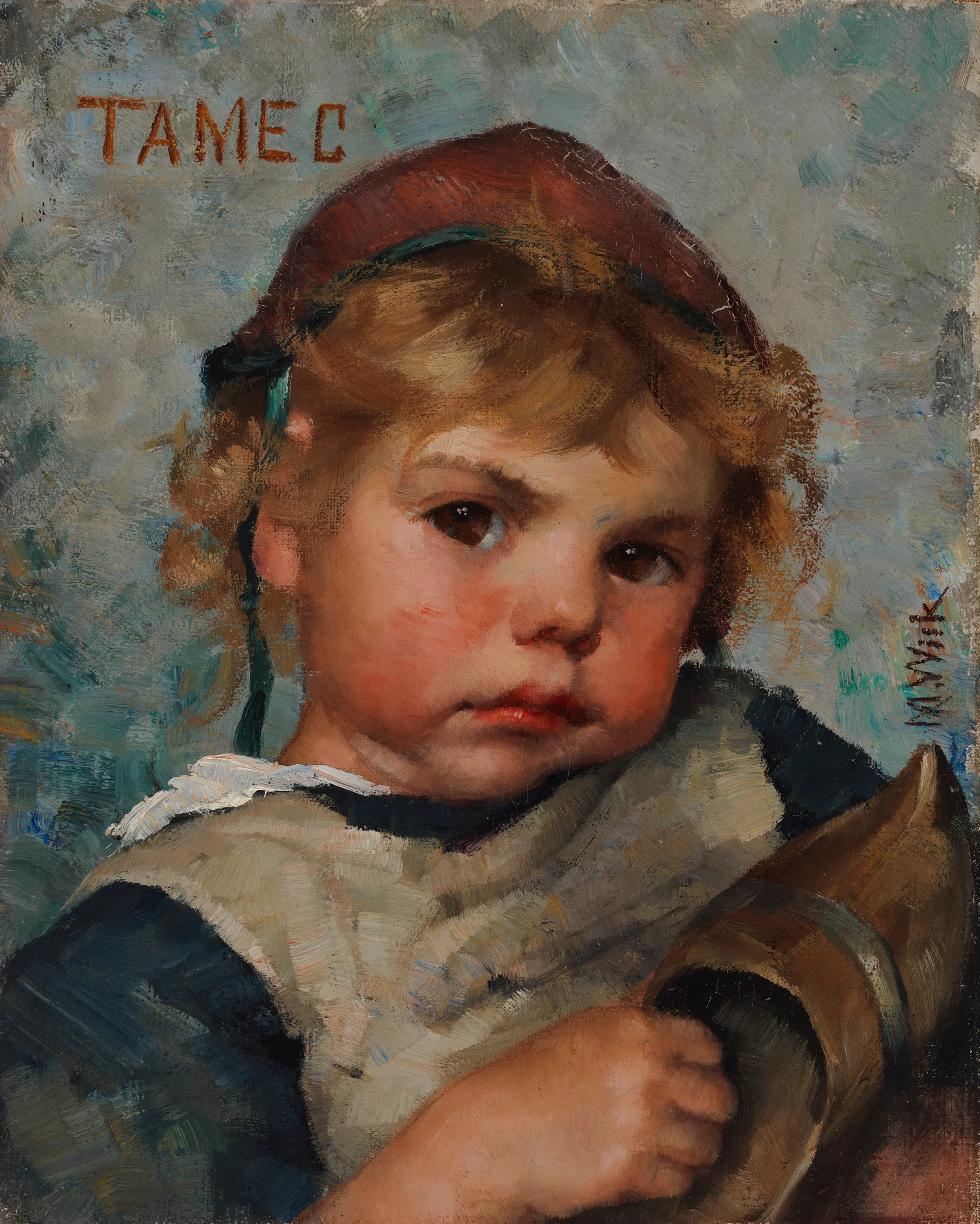

Efforts to increase awareness of female Nordic artists were brought into the conversation as a case study that demonstrated the catalogue raisonné form is just one component of a multi-institutional approach needed to better represent those erased from history. Dr. Susanna Pettersson, CEO of the Finnish Cultural Foundation, argued that bringing women back into the history of art requires widespread, coordinated efforts from institutions of various types. But more than that, it’s about whether or not societies are receptive to such efforts. She noted that efforts to bring exhibitions of Maria Wiik, Hanna Pauli, Elin Danielson-Gambogi, and other Nordic artists across other geographies have had only limited success until recently. But now, exhibitions, catalogues, traveling shows, and books focusing on these artists are gaining traction. Their success is dependent on wider social factors that art historians cannot control.

Lucy Myers from Lund Humphries completed the conversation by sharing publishing data that indicated that women artists' monographs are currently commercially viable, and that two of its nine catalogues raisonnés published in recent history were about women.

Recovering lost collectors: "Do Women Collectors Disappear from Catalogues Raisonnés?"

Because provenance history operates at the center of catalogue raisonné work, the conference brought together a series of case studies that demonstrated how women get written out of records. It specifically examined how women collectors' contributions have been systematically minimized or attributed to their male family members. Common examples of obfuscation include tax issues, families changing the record of donation, and husbands taking credit for their wives’ work. Berthe Palmer was mentioned as the typical example of a female collector whose name rarely appears in documentation because her husband signed the checks while she did the work of collecting.

A portrait of Helene Kröller‑Müller, circa 1905‑10. Photo: Archive Kröller-Müller Museum

Lillie P. Bliss, c. 1924. The Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York

Two panelists spoke at length about the lives of individual female collectors whose contributions have been obscured. Chris Riopelle shared the history of Helene Kröller-Müller, an important collector and museum founder. Kröller-Müller discovered van Gogh early in his popularity, buying her first painting in 1908 and eventually amassing ninety paintings and two hundred drawings with first choice on available works. She expanded her collecting, especially with neo-impressionists, and decided to build a museum in 1911. She commissioned designs from van de Velde and Mies van der Rohe, envisioning sculptures of Seurat and Nietzsche in the collection because she considered Nietzsche and van Gogh kindred spirits. When her husband went bankrupt, the "provisional" museum was the only one built. She was named director in 1938 and died the following year. Despite the collection being entirely her project, credit lines went to her husband—a practice Riopelle noted he could not explain.

Dr. Irene Walsh discussed Lillie P. Bliss, co-founder of the Museum of Modern Art and contemporary of Kröller-Müller. Both came from mercantile families of high status with no family history of art collecting, and both began collecting around the same time. For Bliss, the 1913 Armory Show proved pivotal in her turn toward modern art, transforming a private passion into public service. Her approach was anchored by major works by Arthur Davies and Cézanne, working with a wide range of dealers and maintaining a "buy and hold" philosophy. Bliss died shortly after MoMA opened, which partially explains why she receives less attention than other founders. Significantly, she had her papers burned at her death, making research particularly challenging. Her estate inventory proved invaluable for reconstructing her collection, which was almost entirely bequeathed to MoMA in 1931 and formed the core of the museum's collection.

Dr. Susanna Avery-Quash presented the National Gallery’s projects to elevate women artists, donors, subjects, and former employees, originating in the Women and the Arts Forum. Its activities include the Anna Jameson Lecture Series and the circulation of works by female painters, such as the presentation of an Artemisia Gentileschi painting in a women’s prison. These programs generate funding, build networks, and produce research published online for scholarly use.

Reimagining foundation models for catalogues raisonnés: “What are alternative support models for catalogues raisonnés?”

Catalogue raisonné, as a publication format, must always contend with financial questions, its own financing needs, and, as a cornerstone of the art market. The afternoon's second panel explored alternative support models for catalogues raisonnés, focusing on artist-endowed foundations. Lisa Le Feuvre from the Holt/Smithson Foundation posed questions about the catalogue raisonné's function: Is it a symptom or a cure of oppressive systems? What does it mean for an artist to be "represented" if there isn't a market for their work?

Dr. Douglas Dreishpoon from the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation discussed what he termed "dancing with the elephant": the relationship between scholarship and the marketplace. His mention that traditional boundaries have become "extremely blurred" led to discussions about resale royalties, the role of archives in catalogue raisonné projects, and relationships with market forces.

Christa Blatchford from the Joan Mitchell Foundation outlined the foundation's approach to catalogue raisonné work. The Mitchell Foundation aligns its catalogue raisonné with stated values of artist-centeredness, generosity, and equity. By publishing in both digital and print formats, incorporating outside experts, and including multiple perspectives, the foundation structures its catalogue raisonné to focus on the artist rather than solely on objects. Their work mapping the field of legacy work addresses questions about how artists retain agency over their legacies and what community-built catalogues raisonnés might entail.

Technological innovation and archival expansion: “Innovative approaches to catalogues raisonnés to elevate underrepresented artists and art”

The third panel examined approaches to elevating underrepresented artists through technological and methodological developments. Professor Lynn Rother focused on the technical approaches and addressed challenges in provenance histories from the standpoint of data best practices. While catalogues raisonnés contain valuable information, most present it in free-text fields that resist machine reading. Rother emphasized the importance of structured, machine-readable data linked across systems like GND, ULAN, and WikiData. Without consistent data structures, knowledge remains difficult to aggregate, analyze systematically, and share between institutions.

On methodological practices, Dr. Anne Helmreich from the Smithsonian's Archives of American Art outlined strategic collecting initiatives implemented since 2014 to increase its resources related to underrepresented groups, including feminist, Latino, African American, and Asian American Pacific Islander initiatives. She noted that the Archives does not purchase collections; instead, it accepts donated materials. Helmreich noted that scholars and estates select the institution for its archives based on the Smithsonian’s commitment to critical cataloging and preservation and its transparent approach to processing and cataloguing materials to prioritize accessibility.

Image: Rose Palmer of Wild Rose Studios

Living artists shaping their histories with legacy provisions: the Cindy Sherman Legacy Project

The spotlight session with Margaret Lee discussed the Cindy Sherman Legacy Project and, more widely, explored how living artists can structure their own documentation for future research. The project addresses challenges specific to photographic media, where deterioration can significantly alter how works appear decades after their creation. Sherman observed prints from the 1980s that no longer resemble their original state, raising questions about authenticity and artistic intent when materials age. By establishing clear protocols that she can oversee directly, Sherman creates a framework that can continue after her lifetime. The project maintains the integrity of Sherman's work by creating new photographic prints from original negatives using traditional fiber-based techniques, with documentation of all processes. Each new print receives a Legacy Project label with production date and signature, while returned originals are cut into quarters to preserve materiality for study while preventing future exhibition. (Museums are allowed to retain their originals.) This model of artist-led legacy stewardship attempts to self-fund the catalogue raisonné process through administrative fees.

The project represents a significant shift for living artists contemplating legacy structures. Rather than leaving decisions about conservation, reprinting, and documentation to future estate administrators who may lack direct knowledge of the artist's intentions, Sherman actively shapes these protocols. The administrative fee structure—waived for museums but applied to private collectors—reflects an attempt to create sustainable funding for ongoing catalogue raisonné work without relying solely on external foundation support or sales of estate holdings.

For other artists working in time-based, ephemeral, or materially unstable media, the Sherman model offers a template. It demonstrates how living artists can establish transparent processes for addressing conservation challenges, document their technical methods while institutional knowledge remains accessible, and create self-sustaining financial structures for legacy work. The project also raises important questions about authorship and materiality: if an artist authorizes and oversees the creation of new prints from original negatives, replacing deteriorated earlier prints, where does the "original" reside? In the physical object or in the artist's continued engagement with realizing their vision?

Image: Rose Palmer of Wild Rose Studios

The challenges of documenting ephemeral artists and new digital tools: “A reluctant raisonné-ist”

Professor Mary Jane Jacob began her closing keynote, "A Reluctant Raisonné-ist," by thanking everyone in the room for their scholarly perseverance—an acknowledgment that resonated after a day of presentations examining the complex, often frustrating challenges of catalogue raisonné work. The "reluctant" stance in her title addressed an ongoing methodological tension that she knew well: catalogues raisonnés serve functions for scholarship, markets, and institutional validation, but the form may inadequately represent artistic practices that fundamentally challenged notions of the art object. Jacob's approach to curating artists like Gordon Matta-Clark, who transformed documentation into artwork and preserved fragments of dissected houses, or collaborative projects with distributed authorship, required reconsidering what constitutes the work and, therefore, what constitutes a catalogue raisonné.

This tension informs her work as director of the Magdalena Abakanowicz catalogue raisonné. Abakanowicz worked across diverse materials as they became available, from three-dimensional fiber works to humanoid sculptures reflecting themes of anonymity and mass influenced by Communist Poland. The artists also kept comprehensive documentation and operated from a pronounced sense of history. Jacob chose to create a digital catalogue raisonné to bring all of these materials together. The catalogue raisonné employs Navigating.art for digital publication and includes extensive documentation beyond finished works, recognizing that traditional object-focused cataloguing proves insufficient for practices involving transformation, process, and material experimentation.

Jacob's presentation posed methodological questions about adaptation. If catalogue raisonné methodology developed to serve artists working in stable media with clear attribution and material permanence, how must it accommodate practices that resist these parameters? Digital platforms provide structural flexibility for video documentation, process materials, and collaborative credits that print formats cannot readily include. Jacob concluded by situating catalogue raisonné work within an ethical framework: scholars maintain artists' legacies after death, functioning as stewards of artistic memory who ensure creative contributions endure beyond individual lifetimes.

Questions raised by a field in transformation

Throughout the day's presentations, several recurring tensions emerged that suggest directions for ongoing scholarly inquiry. How can catalogue raisonné scholarship address the paradox that documenting previously excluded artists risks reconstituting the hierarchical structures that produced their exclusion? If, as Pollock argued, catalogues raisonnés simultaneously serve critical scholarship and capitalist market values, can the form be reformed to prioritize the former? What constitutes adequate documentation for artistic practices that resist traditional notions of authorship, materiality, and permanence? And can digital platforms provide genuine methodological flexibility or merely replicate print limitations? How should living artists balance transparency about conservation practices against market concerns, and what models can sustain catalogue raisonné work for artists without market demand or institutional backing?

The conference demonstrated that catalogue raisonné scholarship increasingly involves collaboration among scholars, curators, foundation directors, publishers, legal professionals, and artists. How these collaborative models can address the field's fundamental tensions—between documentation and interpretation, market service and critical scholarship, inclusion and hierarchy—remains an open question. As catalogue raisonnés function as provisional documents rather than definitive statements, the field continues to examine how scholarship can acknowledge its own limitations while serving as stewardship of artistic memory for previously marginalized artistic production.