Demystifying metadata: a practical introduction for art researchers

Auguste Renoir, Still Life with Peaches and Grapes, 1881, oil on canvas, 21 1/4 x 25 5/8 in. (54 x 65.1 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Image in the public domain.

Understanding metadata and its role in digital art history

Although metadata plays a foundational role in digital art history methods, the concept is often overlooked or misunderstood. This guide clarifies what metadata is, why it matters, and how it can transform the work of art historians, particularly those engaged in creating digital catalogues raisonnés and working with scholarly databases.

Understanding metadata is not merely a technical exercise; it is a gateway to more effective research, enhanced collaboration, and the preservation of cultural heritage.

Data vs. metadata: a critical distinction

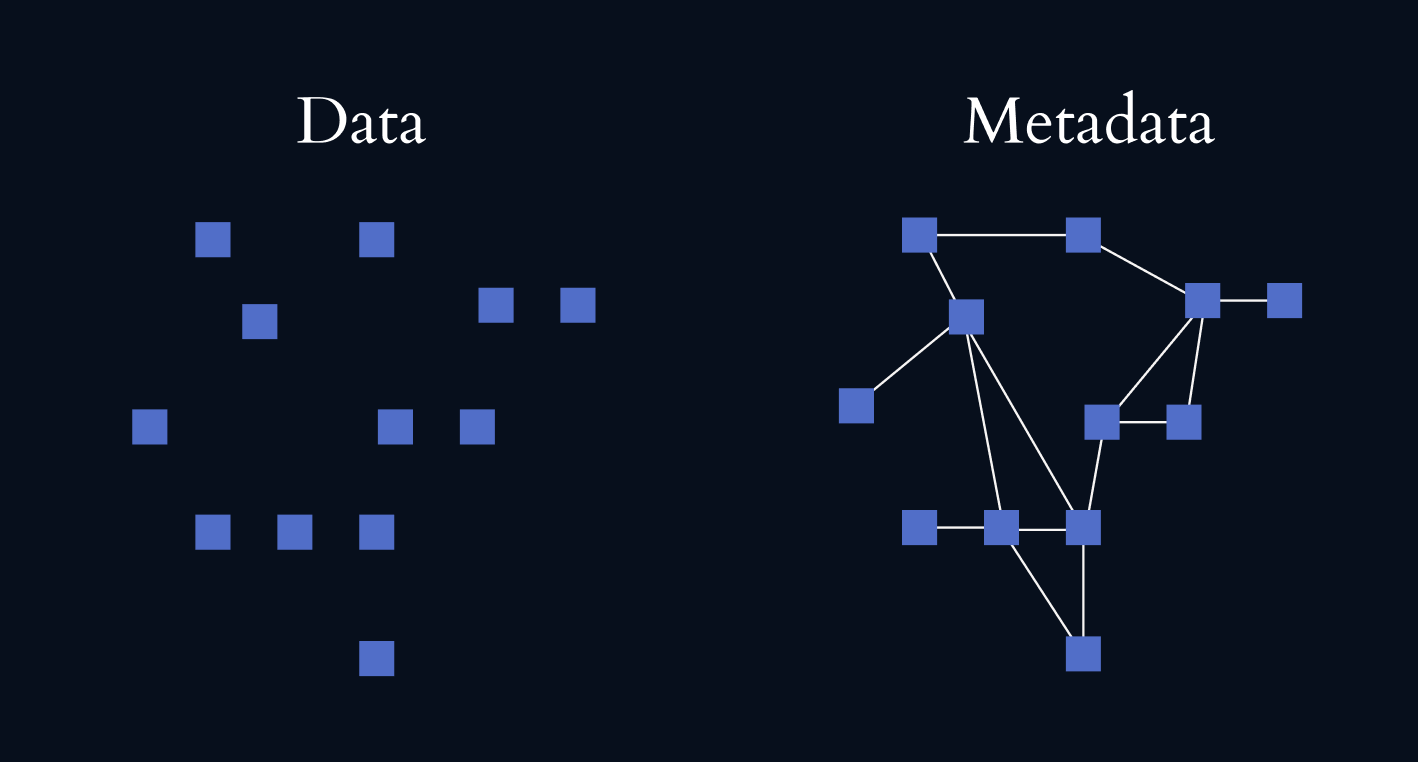

To appreciate the significance of metadata, it is helpful to first distinguish between data and metadata. Data refers to information being recorded or analyzed. For example, the title of a painting, the name of its creator, its dimensions, or its current location. Metadata, on the other hand, provides context and structure to this data. Metadata might indicate when and by whom this information was entered, whether the painting’s title is the original or a translation, or the authority source for the artist’s name.

Imagine a digital record of a painting by Claude Monet. The painting's title, Water Lilies, and the date of its creation, 1906, constitute the data. The metadata might include information about the source of this data — was it derived from a museum catalogue or an auction record? It might also describe how the information is formatted, such as the use of ISO standards for dates. By embedding such metadata, the record becomes not just a repository of facts but a tool for rigorous analysis and discovery.

The distinction between data and metadata becomes even more vivid when considering how metadata enriches the experience of exploring art collections online. Take, for example, a digital exhibition of Impressionist paintings. The data might include high-resolution images of each artwork, accompanied by their titles and dimensions. Metadata adds layers of context: it can indicate the dominant colors in each painting, making it possible to group works by their palette; it can link paintings to historical events, showing how Monet’s works correspond to the Paris World’s Fair of 1889; and it can connect related artworks, such as preparatory sketches or different versions of the same composition.

Schemas, ontologies, and controlled vocabularies

Metadata is often described as "data about data." While this definition is accurate, it does little to convey the richness and utility of metadata in practice. Metadata comes with a host of helpful concepts and tools for organizing and exchanging it, such as schemas, ontologies, and controlled vocabularies.

Schema: organizing metadata

A schema serves as a blueprint for structuring metadata, offering clarity and consistency in how information is recorded. Think of a schema as a predefined set of rules or templates that guide how data is described and organized. For example, Lightweight Information Describing Objects (LIDO) is a metadata standard designed to help museums and cultural institutions share information about their artifacts and objects online. It provides a framework for describing various attributes of objects, such as their title, creator, date, medium, and provenance. This standardization is critical for facilitating interoperability between systems and enabling meaningful searches. When an art researcher uses a schema, they can be confident that the metadata for a painting created in one institution will align more easily with metadata from another, regardless of geographical or organizational differences.

Ontology: establishing relationships between pieces of data

An ontology extends the functionality of metadata by defining the relationships between different pieces of data. Think of it as a map that connects concepts and establishes how they relate to one another. In art research, an ontology might link an artist to their works, where they made it, and where it was sold. This relational structure allows researchers to explore connections that might not be immediately apparent, offering deeper insights into the context and impact of an artist’s work. By using ontologies, digital catalogues raisonnés and databases can evolve into dynamic, interconnected resources that support sophisticated queries and analyses.

Metadata and controlled vocabularies

Controlled vocabularies are essential tools for ensuring consistency and precision in metadata creation. They consist of standardized terms that describe concepts unambiguously, reducing the risk of misinterpretation. For example, the term "oil painting" might have multiple colloquial variations, but a controlled vocabulary ensures that all records use the same term, facilitating accurate searches and comparisons. In art research, vocabularies like the Getty Vocabulary Program’s Art & Architecture Thesaurus (AAT) provide a shared language for cataloguing. By aligning metadata with controlled vocabularies, researchers can enhance the clarity and interoperability of their datasets, making them more useful for collaborative projects and advanced analyses.

The importance of metadata in digital catalogues raisonnés

Art researchers involved in projects like digital catalogues raisonnés need to understand metadata because it underpins the functionality and integrity of their work. A catalogue raisonné is more than a list of an artist’s works; it is a critical, scholarly resource that demands precision and transparency. Metadata ensures that the catalogue can fulfill these demands.

Metadata enables researchers to track the origin of information, identify gaps in the record, and standardize entries for easier comparison and retrieval. In the hands of a skilled researcher, metadata can reveal hidden connections and insights. For example, linking a painting to its exhibition history through metadata might uncover how critical reception evolved. Similarly, metadata documenting the materials and techniques used in a painting could illuminate an artist’s interactions with contemporaneous technological innovations.

Consider provenance research specifically. Metadata can capture not only the names of previous owners but also the circumstances of each transaction, such as sales at auction or transfers during wartime. This information is crucial for resolving questions of authenticity and restitution. A digital record with detailed provenance metadata becomes a powerful tool for researchers, lawyers, and cultural institutions alike.

Searchability and interoperability: the practical benefits of metadata

One of the most significant benefits of metadata is its role in facilitating searchability and interoperability. In a traditional, print-based catalogue raisonné, finding all of the information derived from a specific exhibition catalogue might require flipping through hundreds of pages and referencing a complicated index. In a digital catalogue with well-structured metadata, this task happens seamlessly, delivering results in moments.

Moreover, metadata enhances interoperability, or the ability of different systems and datasets to work together. This is especially crucial for collaborative or interdisciplinary projects. Imagine a scenario where researchers are comparing Monet’s works with those of his contemporaries using data from multiple institutions. Without standardized metadata, inconsistencies in measurement formats could create confusion. One institution might record dimensions as “65.2 x 92.4 cm”, another as “92.4 cm x 65.2 cm (H x W)”, while another might list them in inches or round the values differently. These discrepancies make it harder to compare works accurately and could lead to errors in research or digital reconstructions. By adhering to metadata standards and best practices, researchers ensure that their work can be shared, cited, and built upon by others. This collaborative potential is particularly exciting in the context of digital art history, where the synthesis of diverse datasets can lead to new discoveries and perspectives.

Metadata, digital preservation, and accessibility

Metadata also supports the sustainability and preservation of digital art history projects. Unlike print catalogues, which have a fixed form, digital resources require ongoing maintenance. Over time, software platforms may become obsolete, and file formats may change. Metadata provides a roadmap for future archivists, documenting how the data was created and structured so that it can be migrated to new systems without loss of information. For example, metadata might specify that dates are stored in the YYYY-MM-DD format, ensuring that future users understand how to interpret the data.

Beyond these practical considerations, metadata has a profound impact on the accessibility and inclusivity of digital art history. For those with disabilities, metadata can provide alternative text descriptions for images, making visual content accessible to screen readers. Similarly, metadata can include translations, keywords, and other aids to make resources usable by a global audience. In this way, metadata aligns with the broader goals of digital humanities to expand access to knowledge.

Conclusion: unlocking the potential of metadata

For art researchers working on digital catalogues raisonnés or other digital projects, understanding metadata is not optional; it is essential. Metadata is a dynamic and transformative force that enhances the rigor of scholarship, fosters collaboration, and ensures the longevity of cultural heritage. Researchers can unlock its full potential by demystifying metadata, paving the way for richer and more interconnected art histories.